Turnings Things Upside Down

Have you ever noticed how some postures look similar if you look at them from a different angle? Do you find a posture particularly challenging and wonder if there’s another variation?

One of the simplest ways to vary a posture is to change its orientation. For example, practising a standing or seated posture lying down or vice versa. Changing the orientation of a posture can let you experience the same benefits or it might present you with different sensations or challenges.

This post details variations I’ve offered in class. Maybe there’s a variation that feels right for you, or maybe you’ll be inspired to find your own!

Variations I’ve offered in class

Standing balances

A standing balance develops physical strength to create stability. This strength is developed by creating a sense of anchoring our foot (or feet) to the ground and pushing away to lengthen through the body.

How do we create this sensation lying down? Place your foot against a wall or bedhead. Alternatively, flex the ankle, push through the heel and lengthen through the back of the leg.

Practising standing balances lying down also provides opportunities to experience other sensations of the posture. And there’s no reason why the posture need to be practised supine.

Consider balances like Tree and Open the Gate. Practised supine, these postures can let you experience the sensations of opening the hip instead of focusing on the balance. Practised lying on your side can strengthen the core, hip and gluteal muscles.

Standing and supine variations of ‘Open the Gate’

Standing and prone variations of Dancer

The Dancer posture is a standing balance that really can’t be practised lying on your back. Practised side-lying or prone, you can experience:

Engaging the hamstring to bend your knee to bring your foot close to your buttocks

Stretching the thigh by using a strap or your hand to hold the foot and then bringing your knees in line

Bending the back and opening the front by pushing your foot into your hand or the strap

Cobra

Prone and standing variations of cobra

Lying down postures are not comfortable for everyone. So, why not imagine that the wall is the floor?

Cobra and sphinx are examples of how a prone variation can be practised standing with hands against the wall.

Balancing cat

Balancing cat

Balancing cat (also known as quadruped) helps strengthen the abdominal muscles, lower back, gluteal muscles, thighs and hamstrings. If balancing on your hands and knees is uncomfortable, think about turning the posture upside down and practise dead bug.

Dead bug

Dead bug also helps strengthen the core muscles.

Standing and seated variations of balancing cat/dead bug

Or maybe, flip the posture by 90 degrees and perform a standing or seated variation, which can also help strengthen the core but also develop balance.

Happy baby

Happy baby is a posture I like to use at the end of a class to calm the mind. It can also improve hip mobility, stretch the hamstrings, and even strengthen the arms.

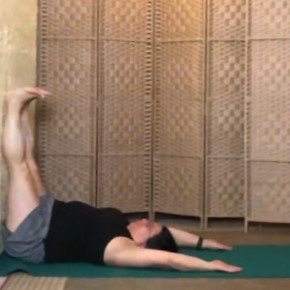

Spinal column posture extending one and both legs

For something different, you might like to try spinal column posture (meru dandasana). This is a seated variation that introduces balancing into the posture.

Note: My back and shoulders are quite rounded in these images, which could have caused problems in my back. When I practise this posture I usually hold my ankles or behind my knees to activate my back muscles. I could also use a strap (my arm extenders!).

Head-to-knee posture and wide-legged forward fold

Recently, I started to think how these postures could be triggering for some people. So, I now offer head-to-knee posture (janu sirshasana) and wide-legged forward fold as variations of Happy Baby and Spinal Column Posture, which bring the torso towards the leg instead of the legs towards the torso!

Downward dog

Downward dog

Downward dog. It’s a posture that strengthens the upper body, the hands, the wrists; lengthens the spine; and stretches the hamstrings.

If downward dog is part of a sequence like the Sun Salutation, a similar posture or variation might need to be substituted to let the sequence flow.

However, as a standalone posture, changing the orientation might make this posture more accessible while experiencing similar benefits or different sensations. Following are some examples.

Right angle posture

Right angle posture (samakonasana) practised free-standing (without a support) can be quite a strong posture, which primarily strengthens the upper body. Practise with your hands pressing down on the back of a chair or against a wall can let you focus on lengthening the spine and stretching the hamstrings.

Downward dog from the chair

Downward dog from the chair requires balance and core strength, (and a sturdy chair that won’t slip!).

Staff posture with arms extended overhead

Staff posture (dandasana) is generally practised with hands pushing into the hands into the floor or the thighs to create a sensation of length in the spine but there’s no reason we can’t raise our arms above our head.

Practise seated against a wall to support the back and gain feedback on postural muscles.

Practise with your feet pushing against the wall to activate the leg muscles.

Legs-up-the-wall with arms extended overhead

Legs-up-the-wall is an inversion and a relaxation posture.

Create more length by raising the arms overhead and activate the core by engaging the abdominal muscles.

Want to challenge the core muscles? Practise without the wall. Come into the position with bent knees first before slowly extending the legs into the air.

Half handstand with the feet against the wall

You won’t find half handstand in my classes; it’s not a posture that I’m comfortable teaching and should be taught by an experienced teacher. But that doesn’t stop me turning upside down every now and then. It’s a posture that strengthens the upper body, develops confidence, and energises the body.

All these postures rotate downward dog through a vertical plane. But we can get creative! What about a side-lying posture away or next to a wall; hands, feet, back or legs against the wall? 😆

Where to from here?

Next time you encounter a posture in class that doesn’t feel right for you, have a go at turning it around or upside down, and collaborate with your facilitator to find a variation that is comfortable for you.